In 2019, the LPC recommended that workers should become entitled to the National Living Wage (NLW, the highest rate of the minimum wage) at the age of 21 instead of 25. In April 2021, as the first step to achieving this, the age of entitlement was lowered to 23. This meant that 23 and 24 year olds moving to the NLW saw a much higher increase in their minimum wage than other age groups in 2021.

We commissioned researchers from London Economics to look into whether this change had affected how 23 and 24 year olds fared in the jobs market (Lee, Manly, Patrignani and Conlon, 2022). They faced the difficult task of disentangling the effects of the pandemic and the end of the Brexit transition period from the impact of the change in entitlement to the NLW.

The researchers’ main finding was that the change in entitlement to the NLW did not affect how likely 23-24 year olds were to have a job. While employment remained strong, the researchers also found that – compared with their slightly older peers – 23-24 year olds in low-paying occupations worked fewer hours on average following the change.

How should we assess these findings? In this blog, we explain the method used by London Economics and how we can interpret the results. We also talk about the implications for further reducing the age of NLW entitlement to 21 in 2024. Overall, the findings support what we have heard from stakeholders – that 23 and 24 year olds have done well in the labour market since moving to the NLW.

This blog focusses on the main findings of the research. For a full account of the research findings and methodology, you can find a summary in Appendix 2 of our 2022 Report or the full research paper can be found on our website.

What did the researchers do?

London Economics compared outcomes for 23 and 24 year olds before and after April 2021 with outcomes for 26 year olds over the same period. They picked 26 year olds because they had similar trends in key labour market outcomes (such as employment) in the years leading up to the change in age threshold. Although closer in age, 22 year olds and 25 year olds did not always follow the same patterns.

The research hinges on the fact that 26 year olds experienced all the events that 23 and 24 year olds experienced around April 2021, except for the large change in their minimum wage. By comparing two groups who usually follow a similar path, and who are affected equally by events in the wider economy, the researchers can isolate the effects of a policy that changes wages more for one group than the other. In reality, of course, the groups will have differences – for example, they may be more or less likely to work in sectors affected by lockdowns during the pandemic. The researchers take this into account, and ‘control for’ the potentially different impact of region, sector and a range of personal characteristics, such as education level. Importantly, this means that when we talk about changes for 23 and 24 year olds, these are changes relative to (similar) 26 year olds.

What would we see if the minimum wage had an impact?

Most importantly, we should see hourly earnings for 23-24 year olds go up faster than for 26 year olds. We would expect the minimum wage to have a direct effect on wages. It is hard to imagine it has indirect effects on employment or hours, without first having a direct effect on wages.

However, the focus of the research is on some of the possible ‘side effects’ of the policy change. For example, following the change employers may have decided to employ fewer 23 and 24 year olds or employ 23 and 24 year olds for fewer hours. Similarly, some 23 and 24 year olds may have chosen to work more or less.

We would expect any effect to be small. Even before the change, close to 90 per cent of 23 and 24 year olds were paid at or above the NLW, and for these workers the policy change would not have had a direct effect on their wage.

What did the research find?

There was no evidence of an ‘employment effect’. The researchers found that 23-24 year olds were no more or less likely to be employed in the year after they became entitled to the NLW. This finding was consistent across different variations of their model and held for most subgroups.

23 and 24 year olds with jobs in low-paying roles or sectors were more likely to be working part-time following the change. For 23-24 year olds as a whole, the researchers did not find any change in either hours worked or earnings. When they looked at those employed in job roles that are usually low-paid (and so are more likely to be affected by the minimum wage), they found that 23 and 24 year olds were more likely to be working part-time – and therefore fewer hours – than before the change. This primarily affected women.

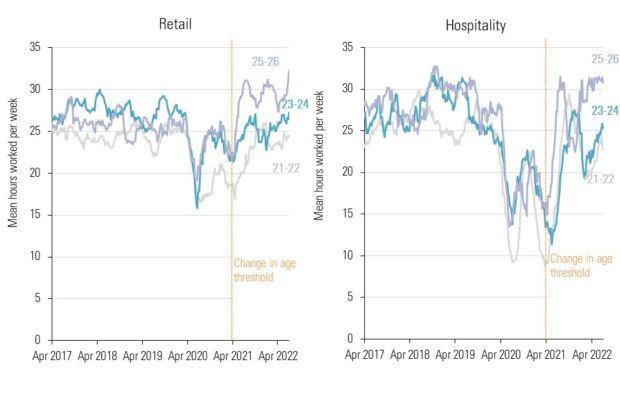

The charts below show how many hours 23-24 year olds and 25-26 year olds worked per on average in the two most important groups of low-paid jobs for young people: retail and hospitality. We can see that average hours worked by 23-24 year olds remained below their pre-pandemic levels for longer than they did for 25-26 year olds. At the same time, 25-26 year olds employed in retail occupations began to work more hours than they had prior to the pandemic.

Average hours worked in retail and hospitality, 21-26 year olds, UK, 2017-2022

See below for source notes.

Did becoming entitled to the NLW cause the reduction in hours worked?

The team at London Economics carefully designed their methodology to try to identify whether the minimum wage change had caused changes for 23 and 24 year olds. However, there are some important caveats to their findings.

We don’t always find the earnings effect that we would expect if the minimum wage caused the change. For example, the strongest negative effect on hours worked is found for women in low-paid occupations (an 8 per cent reduction in hours worked on average), but the increase in hourly earnings for these women is not significantly different from zero. For their male counterparts, meanwhile, there is a significant increase in hourly earnings, but no significant reduction in hours worked. In other cases, reduced hours and increased earnings are found together. The fact that the relationship is not consistent makes it difficult to be sure that there is a genuine causal link between the two.

It is possible for two groups close in age to be differently affected by events – even after applying controls. The researchers compared 23 and 24 year olds to 26 year olds because 25 year olds already had different trends in employment and hours (even after accounting for different characteristics). This shows that closeness in age does not guarantee a similar experience, even without a policy change. This could be because there are differences between the two groups that we can’t measure in the available data.

In fact, when we look at the analysis of young people in low-paying job roles, we see that there was already a significant fall in the hours worked by 23 and 24 year olds relative to 26 year olds in the year before the change in the age threshold. This could be because employers had anticipated the change, but it could also mean that the fall was caused by other factors.

These considerations do not mean we should ignore the findings – there is strong evidence that there has been a shift in patterns of full-time work for different age groups and we should try to understand this. But we should be cautious in saying that the minimum wage caused this change.

So should we be worried?

The changes we see could reflect employers preferring to give hours to more experienced, older workers once 23-24 year olds lost the advantage of a lower minimum wage rate. However, despite the fall in their average hours, 23-24 year olds were not reporting that they wanted to work more hours: the share of workers reporting any kind of underemployment – that they wanted to work more than they currently do, assuming the same pay – was lower following the change than it had been before the pandemic.

We also know that employers were reporting acute labour shortages at this time. For the employers we spoke to, worker shortages were a much more important issue than the change in age threshold. Taken together with low underemployment, this suggests that the results could be capturing changes in the choices made by 23 and 24 year olds, rather than – or as well as – the choices of employers.

If this is the case, it may be a more positive story, but there are nuances to consider. Recent work by the Resolution Foundation (Murphy, 2022) notes that young workers in low-paid jobs often talk positively about working less, but that this choice is made in the face of constraints that make working full-time in low-paid sectors unfeasible, such as requirements to work on evenings or weekends. Murphy (2022) also notes that shifting from full-time to part-time work could affect young people’s future career .

What does this mean for 21 and 22 year olds?

We expect to go ahead with the further change in the age threshold for the NLW – to age 21 – in April 2024. The finding that 23 and 24 year olds’ employment remained strong after they became entitled to the NLW reassures us that it is possible to do this without harming employment prospects for 21 and 22 year olds, and our stakeholders – both employers and workers – continue to tell us that it is the right thing to do.

While 21 and 22 year olds are different to 23 and 24 year olds, most employers already pay 21-22 year olds at the adult rate: 85 per cent of 21-22 year olds were paid at or above the NLW in April 2022. The LPC has recommended a large increase in the 21-22 rate this year, to smooth the transition on to the NLW. This will leave the difference between the two rates at only 24 pence per hour.

Related links: The full paper by Lee, Manly, Patrignani and Conlon; the LPC’s 2022 Report.

Source notes for charts: LPC estimates using LFS microdata, weekly (13-week rolling average), not seasonally adjusted, 21-26 year old population, UK, April 2017 – June 2022. See Appendix 4 of our 2022 Report for a full list of SOC codes included in retail and hospitality occupations. We have included both 25 and 26 year olds to increase the sample size, even though London Economics’ research looked only at 26 year olds.

2 comments

Comment by SUMIT RAHMAN posted on

An excellent write up of some interesting work! But it looks like one of the paragraphs, mentioning 'side effects', is incomplete.

Comment by josephwilkinson posted on

Thanks for flagging - now corrected.