What do workers look for in jobs? Wages are obviously important. If you asked almost anyone whether they would like to be paid more per hour, they would say yes. But new evidence [1] commissioned by the Low Pay Commission shows that wages are not the only thing about a job that affects worker’s wellbeing.

Jobs include a range of non-wage benefits. First, jobs provide monetary benefits outside of core pay, such as shift premiums or pension contributions. Second, the terms and conditions of jobs can vary, such as annual leave policy, flexible working arrangements and guaranteed hours. Finally, the nature of the work matters. Some types of work are more enjoyable than others, although this will depend on individual preferences.

It is hard to measure the value of non-wage benefits, especially as different workers have different preferences over them. This new paper takes an innovative approach by outsourcing the question to workers themselves. The researchers estimate how different occupations impact worker reported life satisfaction between 2013 and 2019. They control for pay and other factors which could also drive life satisfactions such as age and gender.

They find that non-wage benefits from jobs are higher in better-paying work. This means that the rewards from work are more unevenly distributed when we account for all the benefits from that work rather than just pay. This is true across the whole economy and within low-paying sectors. Inequality in the full rewards from work (including non-wage benefits) are double the size in low-paid occupations, compared with the inequality in pay alone across these occupations.

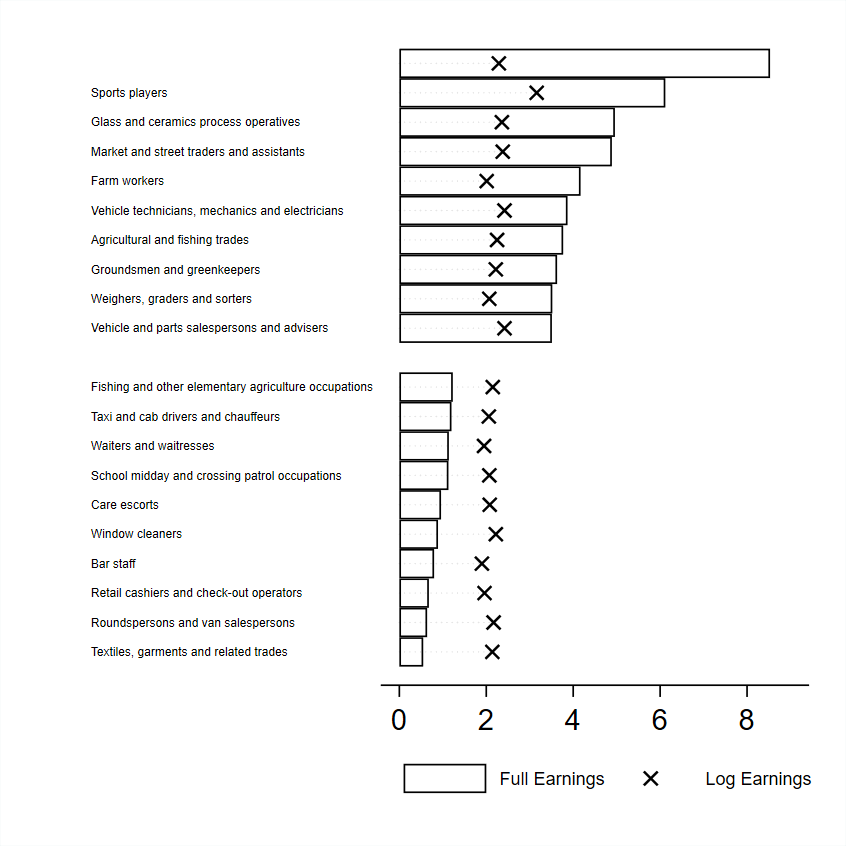

The non-wage benefits from work were larger in occupations which involved working outdoors and were less repetitive. For instance, for sports players and farm workers the value of their “full earnings” (including non-wage benefits) is considerably larger than the benefits from pay alone (labelled in the graph below as “log earnings”). Work in retail and manufacturing tend to have lower measured “full earnings” relative to their pay, suggesting low levels of non-wage benefits in these occupations.

The units for this graph are natural logarithms. The non-wage benefits from jobs are converted to the equivalent of monetary earnings by dividing the impact of occupation on wellbeing by the average impact of log earnings on wellbeing. Full earnings is the sum of non-wage benefits and log earnings.

The authors also find that considering “full earnings” from work rather than just pay increase the gaps between groups of workers. They estimate that the gap in “full earnings” (including non-wage benefits) between women and men is twice as big as the gap between women and men in pay alone. The gap between earnings for white workers and workers from Black or Bangladeshi backgrounds also gets considerably bigger when considering non-wage benefits alongside pay.

Critics might argue that a range of other factors beyond job quality and non-wage benefits affect subjective wellbeing, and the authors cannot control for all of them. If workers who do certain jobs tend to be happier for reasons unrelated to their work, this would bias the estimates of the non-wage returns to work. The researchers try to address this criticism by tracking the same workers over time as they switch jobs. Those checks reinforce their main findings, but the additional analysis was conducted on smaller sample sizes.

This study shows that the quality of a job depends on much more than just its pay. It also shows that non-wage benefits are particularly important for low-paid workers. Employers and policy makers should consider what steps they can take to improve the quality of work for low-paid workers.

One aspect of job quality raised by the Taylor Review of Modern Working Practices [1] was ‘one sided flexibility.’ One sided flexibility can include unreasonable requirements around workers’ availability; unpredictability making it difficult for workers to manage finances; and an overarching fear of losing future work if they raise a concern or turn hours down. To tackle this, in 2018 we recommended that the Government introduce a right to switch to a contract that reflects your normal hours, a right to reasonable notice of your work schedule and compensation for shift cancellation or curtailment without reasonable notice.

We’re interested in your views on job quality and other issues related to low pay. We plan to launch our annual consultation later this year.

References:

[1] Good work: the Taylor review of modern working practices, 2017. Available here: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/good-work-the-taylor-review-of-modern-working-practices

[2] LPC responses to the government on ‘one-sided flexibility’: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/low-pay-commission-response-to-the-government-on-one-sided-flexibility